Seth Godin last week: “When smart people who care get frustrated, something is wrong.”

I had a discussion the other day that should be a wake-up call, if not a bone-chiller, to school leaders. I have started talking to a lot of teachers and administrators about how we can leverage collaboration to more quickly embed new thinking and teaching in the classroom. This was one of those conversations. For obvious reasons I am not going to name the person or school.

“Jane” is a veteran teacher, high school department chair, iconic to most of her peers and almost all of her students. She has always been open to new ideas and has recently engaged her department in a discussion of changing some of what and how they teach. Jane absolutely realizes that the world is changing; that we need to combine traditional knowledge content with an emerging set of skills (call them 21C or NthC skills for ease) if we want to effectively prepare our students for their future. Jane wants to change what takes place in the classroom. She has always been open to innovation. She is a big thinker.

The department has started conversations, and the early results are predictable: some members of the department are eager and others are not. They don’t know what change looks like; they don’t really have a clear image of what they want or where they are going. But all of that is okay with them; they understand that change involves some fear, and that not all of them have to experiment at the same pace. Some can forge ahead and pilot new ideas; others will lag a bit behind and watch to see what happens. That is all good.

Then we started talking about specifics. Keith Evans had shard with me a capstone project they have at the Collegiate School in Richmond that, along with great content, teaches students the skill of discourse, as opposed to debate. I used this example with Jane: what if her department took on “discourse” as a new skill to embed into the curriculum? Would that be of interest? Could that provide some framing as they develop new approaches that seek to enhance skills like collaboration and communication?

Jane hit a stumbling block at that point, and this is the chiller. She loved the idea of teaching discourse, but she did not see how, or possibly even why, a single department or a small group of teachers could or should engage in this discussion. She asked: “Shouldn’t that direction come from the whole school? Is that really my role? Where is the upside for me or my small group to take on the role of “discourse” in our overall program plan?”

As we drilled down in less than five minutes, it boiled down to this: Jane’s school does not have–in fact has never had–a culture or structure for taking a simple idea like this forward without entering into an all-school discussion about it. In fact, Jane is not really sure whose responsibility it is to even start that discussion, or what the process might look like. Remember: Jane is a veteran leader at a highly respected school.

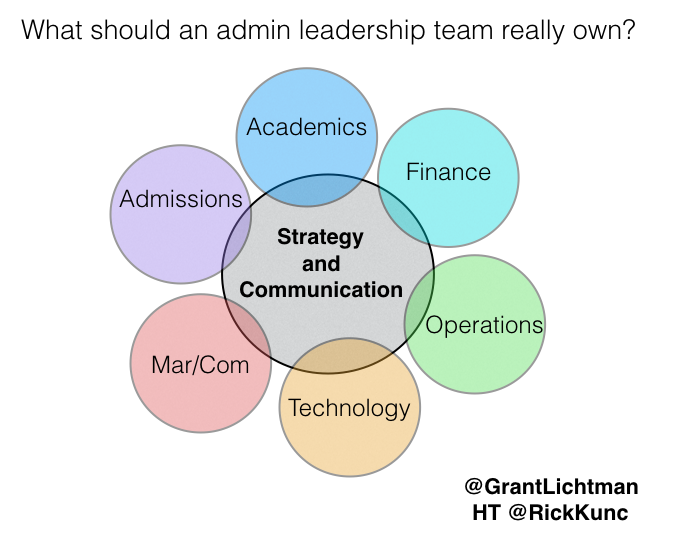

I will not go into all the reasons that this is REALLY bad for any institution. It just re-enforces what many of us are saying: that our schools have structural impediments to change at a time when change is required. Our great educators are great at what they do; they are wonderful people full of passion and dedication, but many do not have the training or natural DNA to process change dynamics. Leadership has to step in and develop the culture and mechanics of change management, and align resources with this critical need. We can teach innovation to our faculty and administrators just like we teach skills to our students. But first we have to make the commitment to do so; it is not going to happen on its own.

Grant, I find it difficult to believe your characterization of the situation. Veteran teacher leaders know how to get things done in their schools and seldom have difficulty making things happen. Ask yourself, who was really enthusiastic about the proposed “discourse” program. Was it you? And I ask you, what is wrong with taking something like that program to the whole school for consideration? Cal

Hard to believe but true. Veteran teachers absolutely know how to get things done within a framework that is familiar to them: traditional departmental decisions about who teaches what, which books to order, and the like. This discussion was not specific to the idea of teaching discourse; it was about changing the expectations of the learning experience from the traditional content to something more skill-based. She did think that such a discussion should take place as an all-school (or certainly all-division) discussion, but felt very uncertain about the mechanics of that. More importantly, no one in the organization had ever clearly said “We want you and expect you as senior faculty to re-imagine your roles and lead this discussion”. That is what is key, because it is that embracing of institutionalizing of innovation that we need.

I do not imply that Jane’s example is representative of all schools and faculties, but I did think the example was relevant and telling.

Thanks for the comment and calling for further explanation!

Grant, Okay. I’ll attempt to dig a bit deeper. As I read my original post I see that I was dancing around what I really wanted to ask, but first. Veteran teacher leaders know how to bend, twist, and if necessary destroy frameworks when they are committed to making change. Been there, done all of that. I understand a bit about the influences of structure on behavior, but there is also the individual and/or small group that can effect radical change when it is desired. So, is it possible that Jane was not interested enough to make “your” change happen and simply and easily laid it off on lack of supporting structure or the lack of management leadership? And I’ll ask again in more general terms, who was enthusiastic about the change? Was it you or what it Jane? Cal

Cal,

Agree that some teachers in some schools do not have this issue; hopefully more than less! In the case I described I am very confident of the dissonance faced by “Jane”. It was not about the “what” of change, but the “how”. The discussion was just started by the idea of teaching discourse, and quickly re-focused, by her, on the question of how and why these types of changes can be brought about. So much of what we need to work on is process in order to become sustainable innovators.